Join the Fun: “Empowered Parents Summit”

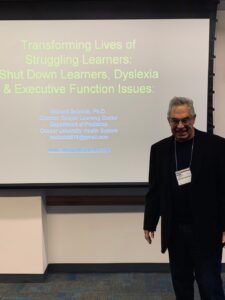

I am honored to be a part of this Empowered Parents Summit. So many great speakers are presenting their view of parenting in the modern era.

I will be talking about issues related to my latest book, “Beyond the Power Struggle: A Guide for Parents of Challenging Kids.”

Here’s the link to the conference – remember it’s free!!! Click Here: Registration Summit Parenting Conference

Feel free to make comment below.

To receive future blog posts, register your email: https://shutdownlearner.com.

To Contact Dr. Richard Selznick for advice, consultation or other information, email: shutdownlearner1@gmail.com.

Copyright, Richard Selznick, Ph.D. 2023, www.shutdownlearner.com.

Copyright, Richard Selznick, Ph.D. 2023, www.shutdownlearner.com.

Those of you following this blog for some time know there are some recurring themes in these posts (that mostly irritate me).

Those of you following this blog for some time know there are some recurring themes in these posts (that mostly irritate me). More and more, parents tell me that their children never get homework.

More and more, parents tell me that their children never get homework. Understanding what children want can bring about a major shift in your thinking. If you embrace this concept, I predict your perceptions will change for the better, which then will impact your child.

Understanding what children want can bring about a major shift in your thinking. If you embrace this concept, I predict your perceptions will change for the better, which then will impact your child. My marketing manager (my daughter Julia) has been pushing me to create more short videos to spread around.

My marketing manager (my daughter Julia) has been pushing me to create more short videos to spread around. I am excited to let you know that the new baby, “Beyond the Power Struggle: A Guide for Parents of Challenging Kids,” has been officially birthed!!!

I am excited to let you know that the new baby, “Beyond the Power Struggle: A Guide for Parents of Challenging Kids,” has been officially birthed!!! Eight-year-old Amelia goes about her day mostly ignoring her mom, Andrea.

Eight-year-old Amelia goes about her day mostly ignoring her mom, Andrea.